From Memory to Modern Day: A Forty-Year Journey with Music Boxes

From Memory to Modern Day: A Forty-Year Journey with Music Boxes

(Author: Muro Box Founder Chen-Hsiang Feng, based on a 2025/02/27 interview with Kyooh General Manager Huang Long-Xi)

Thank you all for the enthusiastic response to our report on the “The Birth Place of Music Box” To give you a deeper understanding of the story of music boxes in Taiwan, we revisited Kyooh and spoke with General Manager Huang Long-Xi.

Kyooh is Taiwan’s only music box factory, with over 40 years of history—from OEM work to innovation, and the establishment of a modern music box museum. It stands as a witness to Taiwan’s industrial transformation. Join us as we revisit Taiwan’s “Music Box Era”:

- The beginnings of music boxes in Taiwan

- Evolution of Sankyo music box product lines and technology transfers

- Market competition and strategies

- The founding of the museum

Too long to read? We’ve prepared a podcast version so you can listen and learn about Taiwan’s music box history:

The Global Music Box Market in the 1970s

Rewinding to the 1970s, the global demand for music box movements was around 98 million units per year, with Taiwan being the world’s largest market, accounting for about 30 million units on its own. Notably, this demand was for export rather than domestic consumption. Taiwan served as the final assembly hub, importing music box movements from Japan or Malaysia. Once installed into crystal balls or doll bodies, they became complete music boxes ready for export worldwide.

This aligned perfectly with Taiwan’s industrial structure at the time: the country had skilled yet affordable labor, allowing imported machine-made components to be assembled domestically at low cost and then re-exported.

At the time, Japan had overcome the technical limitations of mass-producing music box movements. Much like today’s low-cost music box exports from China, Japan used aggressive price competition to devastate all European and American music box manufacturers. Led by Sankyo, five Japanese companies in total—Toyo, Sanyo, Sanshin, Shimizu, and Sankyo—dominated the market, controlling 95% of the global music box industry. But this situation was about to change.

Sankyo Seiki Mfg. Co., Ltd.’s Presence in Taiwan

Sankyo’s sales department suddenly received critical information: since Taiwan was the world’s largest export-oriented music box assembly market in the 1970s, their four competitors were planning to join forces and build a large-scale music box production facility directly in Taiwan. If this is true, it would allow their rivals to further reduce production costs and immediately put Sankyo at a disadvantage in the price war. Although Sankyo had already established a production base in Malaysia, they now had to move quickly to set up a large-scale facility in Taiwan as well.

Reasons for Kyooh’s Factory Establishment and Its Site Selection Process

Due to Taiwan’s regulations at the time, wholly foreign-owned companies were required to export at least 50% of their products. Therefore, Sankyo’s new music box factory in Taiwan had to form a joint venture with a local company in order to sell 100% of its output domestically (sold to distributors, but ultimately exported).

At that time, Sankyo already had an investment in the Kaohsiung Export Processing Zone for producing home appliance components. They approached Taiwan’s Sanho Electric Co., Ltd., which had a technical partnership with Sankyo in timer manufacturing, hoping to leverage their local presence to establish a music box production base. By combining Sankyo and Sanho, the joint venture Kyooh Precision Co., Ltd. was officially founded.

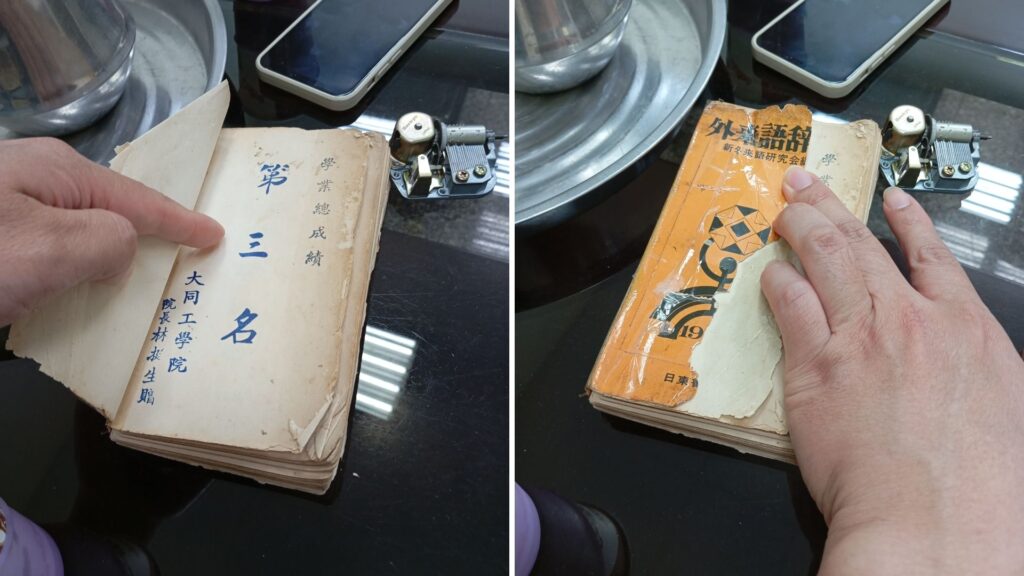

Facing the urgent pressure of competitors planning to jointly produce in Taiwan, the preparation period for Kyooh’s factory was extremely short. Before Kyooh was founded, current General Manager Huang Long-Xi served as the technical section chief at Sanho. Due to a previous industrial design job, he had received three months of Japanese training at Tatung Institute of Technology. With only basic Japanese communication skills, he was sent to Japan for a 21-day internship and immediately returned to Taiwan to prepare for the factory. The company was established in April 1979 and began production by August, illustrating the urgency of the situation.

Initially, Kyooh searched for a factory in the Wugu Industrial Zone in Taipei. However, the existing buildings there had columns in the middle of the floors, leaving insufficient straight-line space for production lines, which did not meet the Japanese side’s requirements for music box assembly workflow. Eventually, because Kyooh’s chairman at the time, Mr. Lin Minshun, was from Wufeng, the company decided to look for a suitable site there. Coincidentally, Dechang Construction was planning the Nanshi Industrial Zone in Wufeng, so after several considerations, Kyooh ultimately settled there.

Negotiations over Management Control between Sankyo and Kyooh

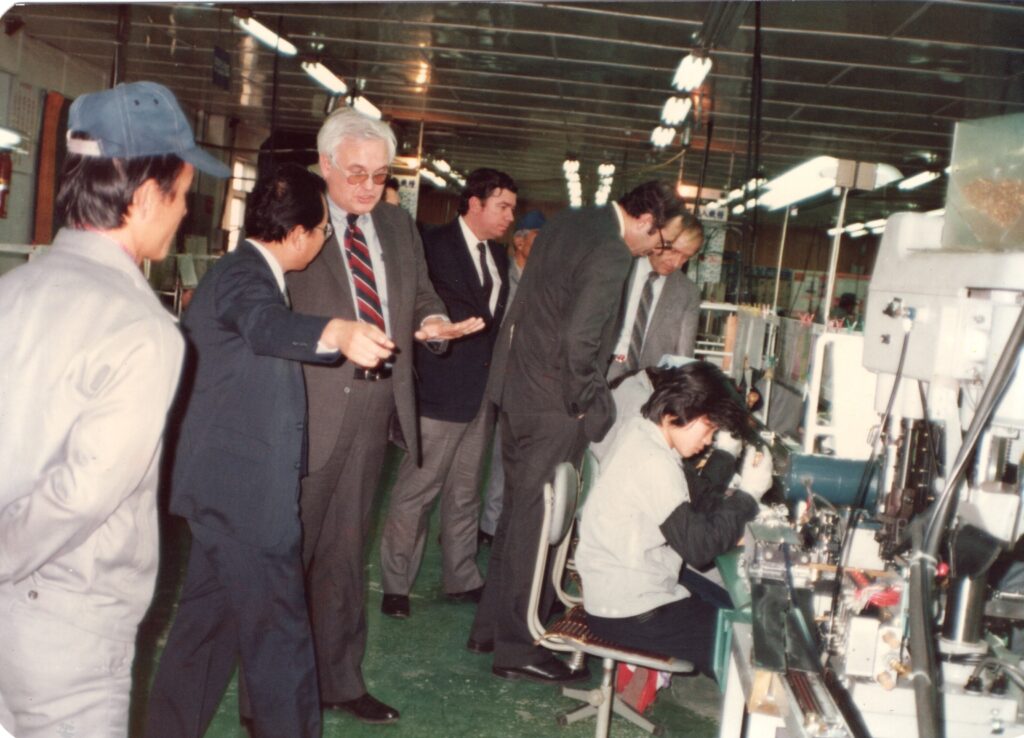

Under Taiwan’s old Company Law, foreign investors in joint ventures could not hold more than 49% of shares, so Sankyo’s initial stake was 49%, below the majority. However, as music boxes were Sankyo’s founding product, the Japanese side was well-versed in management practices for this business. After negotiations with the Taiwanese partners, Sankyo effectively obtained operational control.

As a result, positions from general manager to factory manager and department heads were long-term assignments of Japanese personnel. Japan also regularly sent staff to Taiwan for support and training—periods ranging from three to six months. Although General Manager Huang Longxi was responsible for establishing the factory in Taiwan, his initial title was only “Manufacturing Section Chief.” This reflected the technological advantage of Japanese manufacturing, meaning that even with a majority stake, Taiwanese partners had limited operational influence in boardroom decisions.

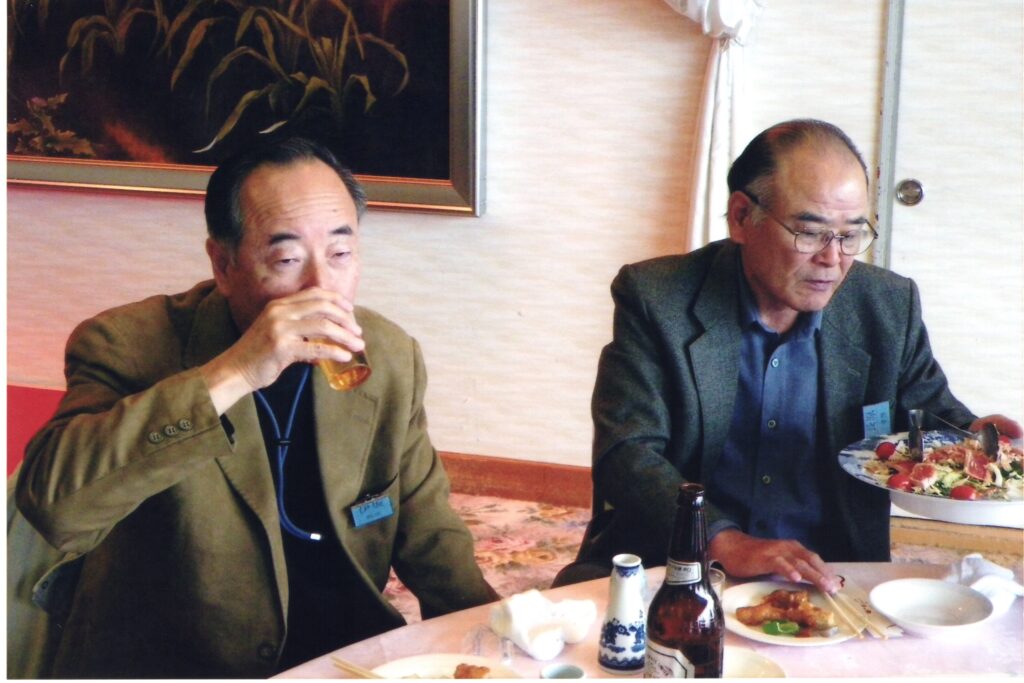

The first several general managers of Kyooh were Japanese. The fourth general manager, Matsushima Hiroshi, was transferred from Sankyo’s Malaysia plant, where he had worked for six years, and then served as Taiwan GM for nine years. The sixth general manager came from Sankyo’s Guangzhou plant. The current general manager, Huang Long-Xi, assumed the role in 2004 as the seventh GM and continues to serve today.

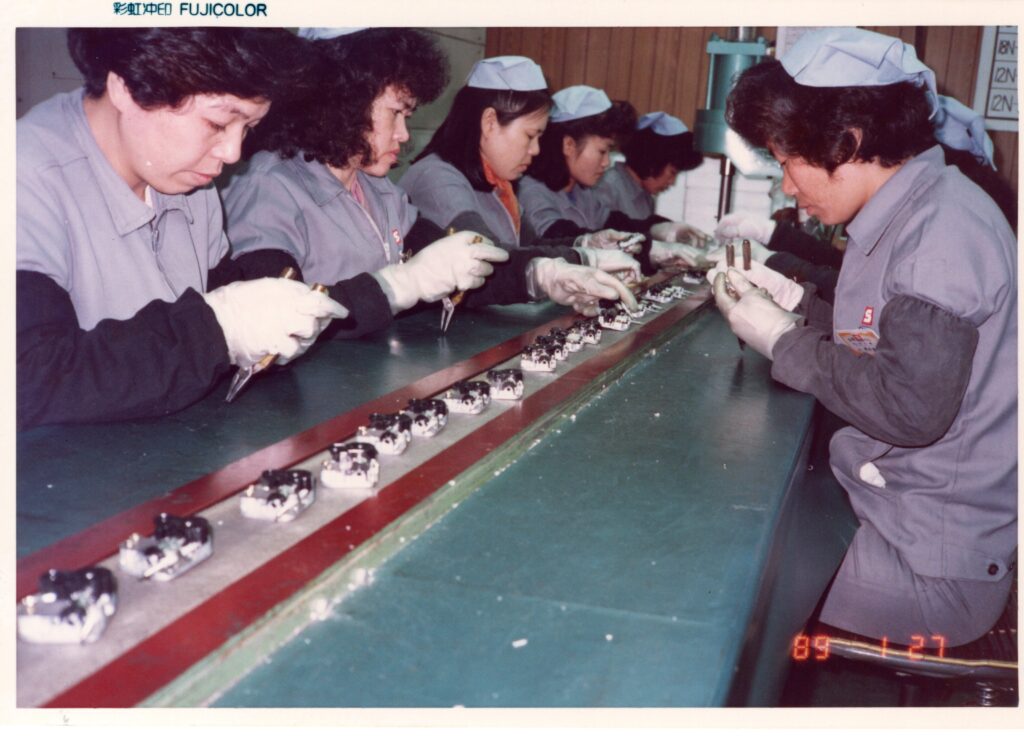

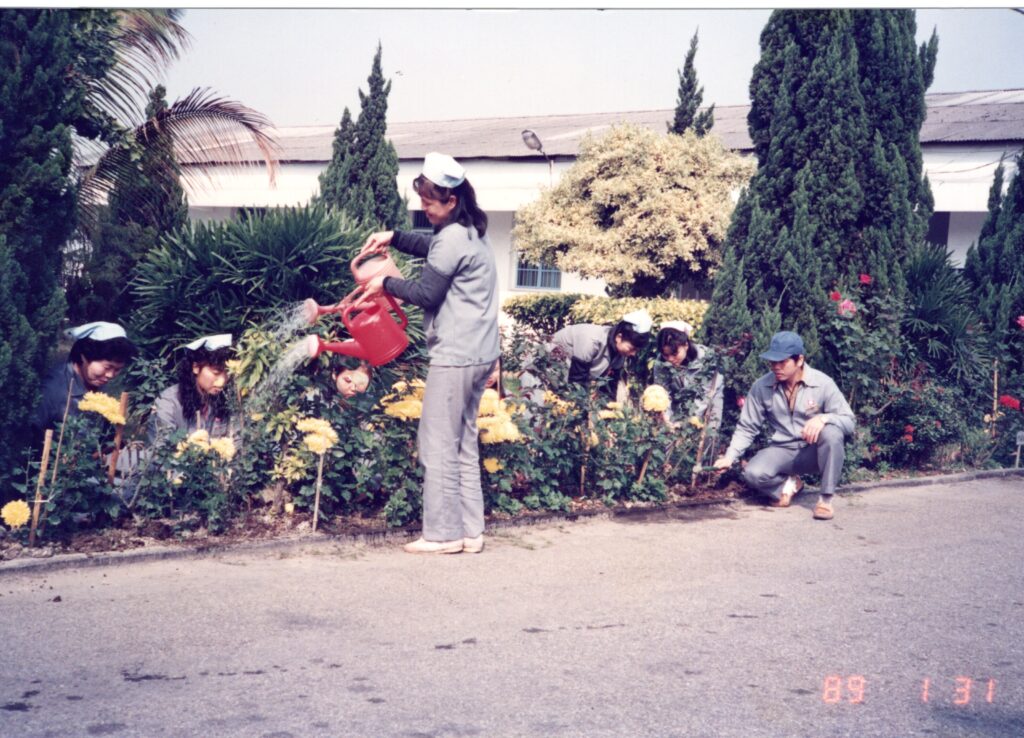

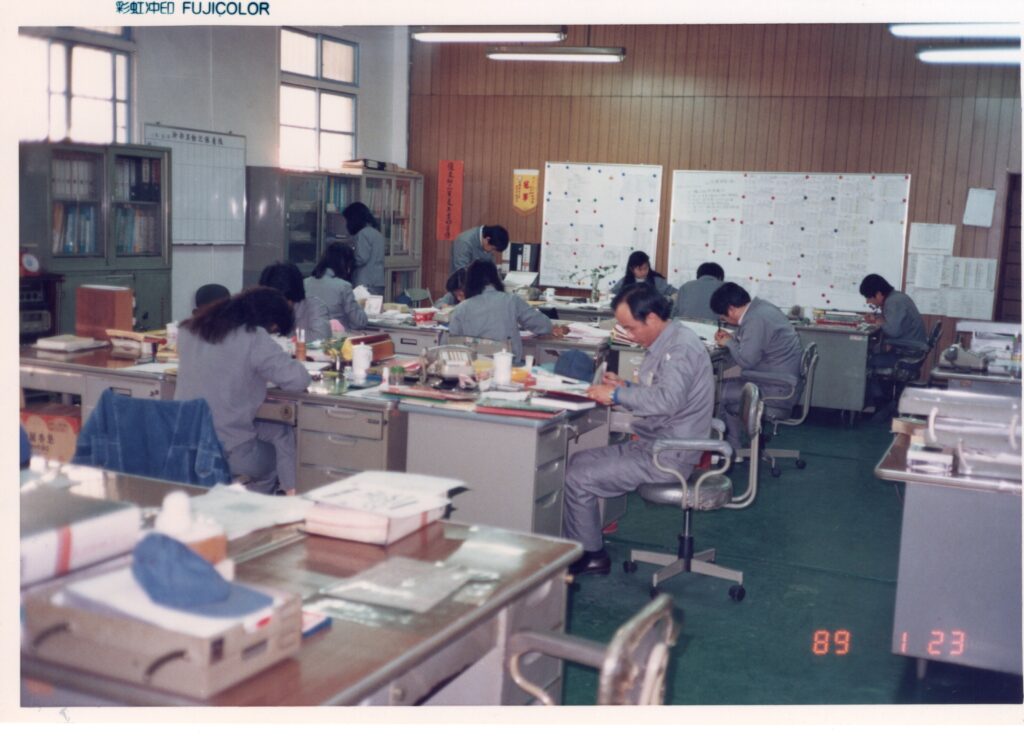

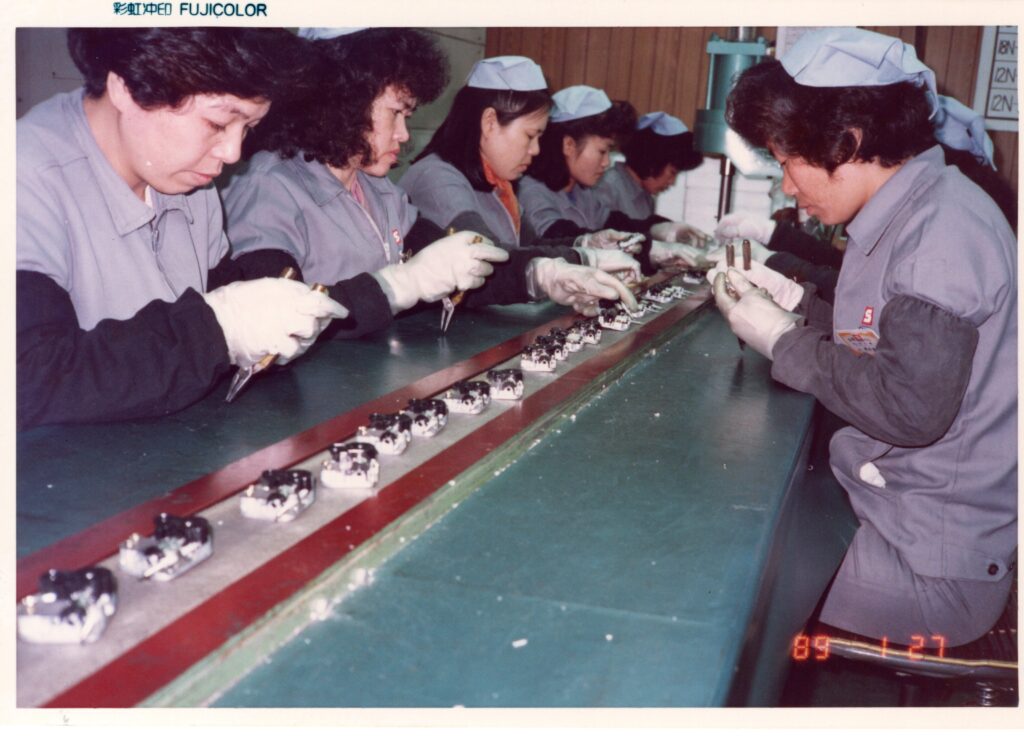

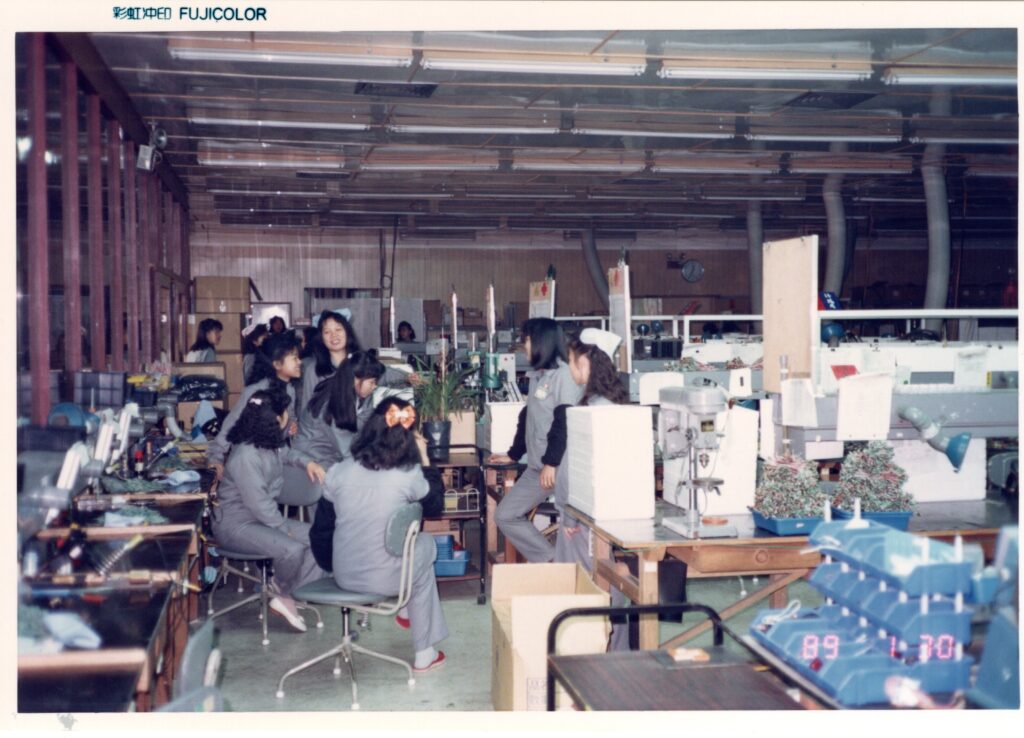

Kyooh’s Early Production Scenes

In its early days, Kyooh’s main business was assembling music box movements, without producing any components—all parts were imported from Japan.

Despite being assembly-only, the Japanese side was very concerned. The factory had been set up in a hurry, and the Malaysia plant had taken six years without turning a profit. The Japanese assumed Taiwan would face a similar situation, creating an atmosphere of extreme pessimism.

Unexpectedly, Kyooh began operations in August 1979, and by the end of the fiscal year in December—just five months later—the company had earned NT$6.8 million! This likely reflected a fundamental difference in worker efficiency. When asked about the reason, the general manager revealed how they had selected their operators at the time.

A Unique Approach to Talent Selection

The general manager mentioned that during operator interviews, he would take black and white Go (the board game) stones, mix them together, and ask candidates to pick black stones with their left hand and white stones with their right hand simultaneously. They had to sort and neatly place the stones into the squares of a Go board. The number of stones placed and the tidiness within a set time were then assessed. Using this unique selection method, all Kyooh operators were quick-eyed, nimble-handed, and meticulous—no wonder the company achieved profitability in just five months!

A Relationship of Collaboration and Calculated Strategy with Japan

From the first year in 1979, Kyooh earned NT$6.8 million in just five months. In the second and third years, profits soared to NT$20–30 million annually. However, earnings gradually declined: in the fourth year, profits dropped to just over NT$10 million and continued to decrease slightly each year thereafter.

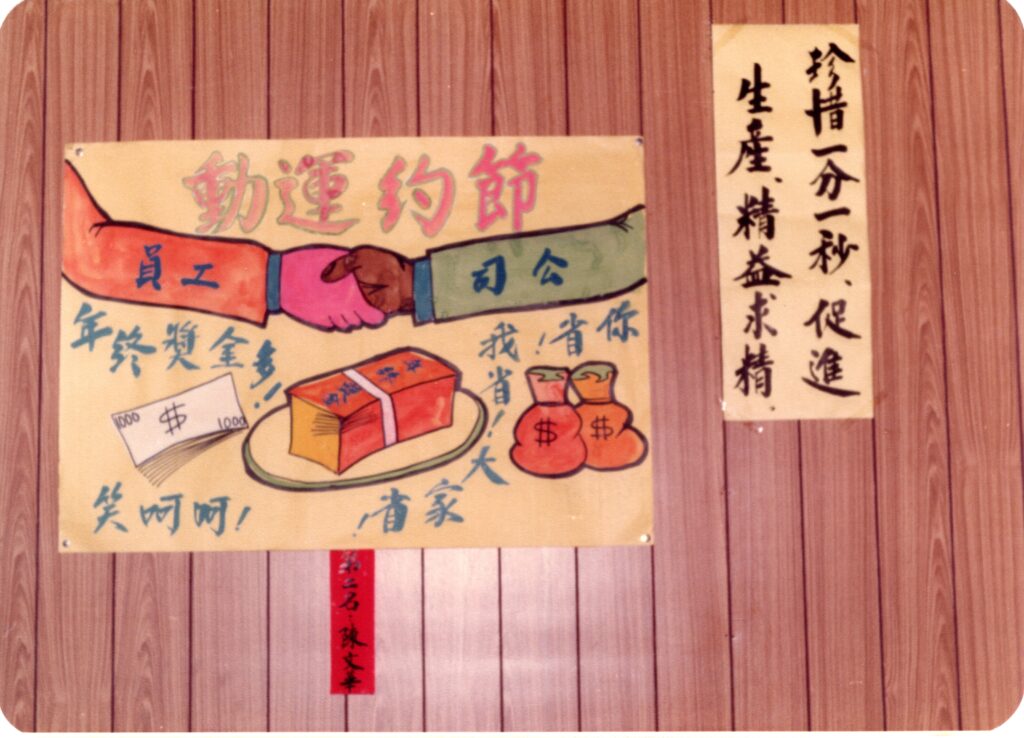

Why? Because production management was entirely assigned by the Japanese side, giving them full visibility of the cost structure. Initially, all raw materials for the music box movements were purchased from Japan. When the Japanese were surprised by the high profitability of the Taiwan plant, they began adjusting export prices of Japanese parts year by year, which gradually reduced Taiwan’s profit margins. In response, the Taiwanese partners launched aggressive cost-improvement initiatives.

Fortunately, the Taiwanese shareholders had insisted on retaining early profits to purchase the factory and land currently in use. This preserved the company’s foundation, allowing Kyooh to maintain valuable assets even after the music box boom faded, providing a safeguard that helped the company weather future challenges.

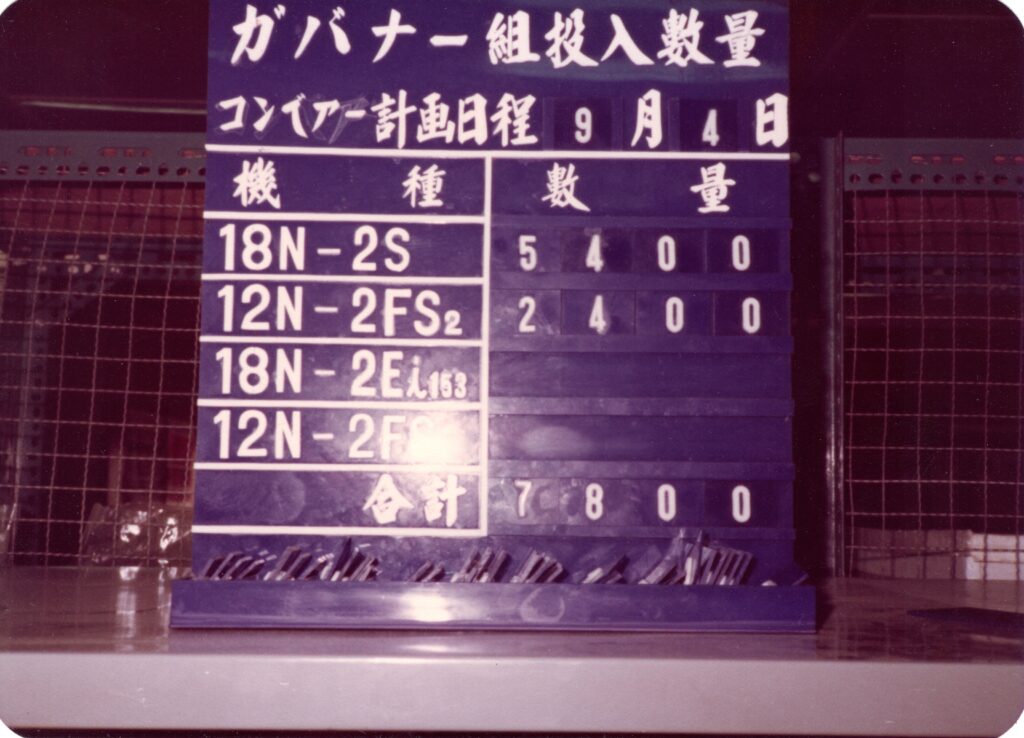

“2S”: Sankyo’s First Music Box Produced in Taiwan

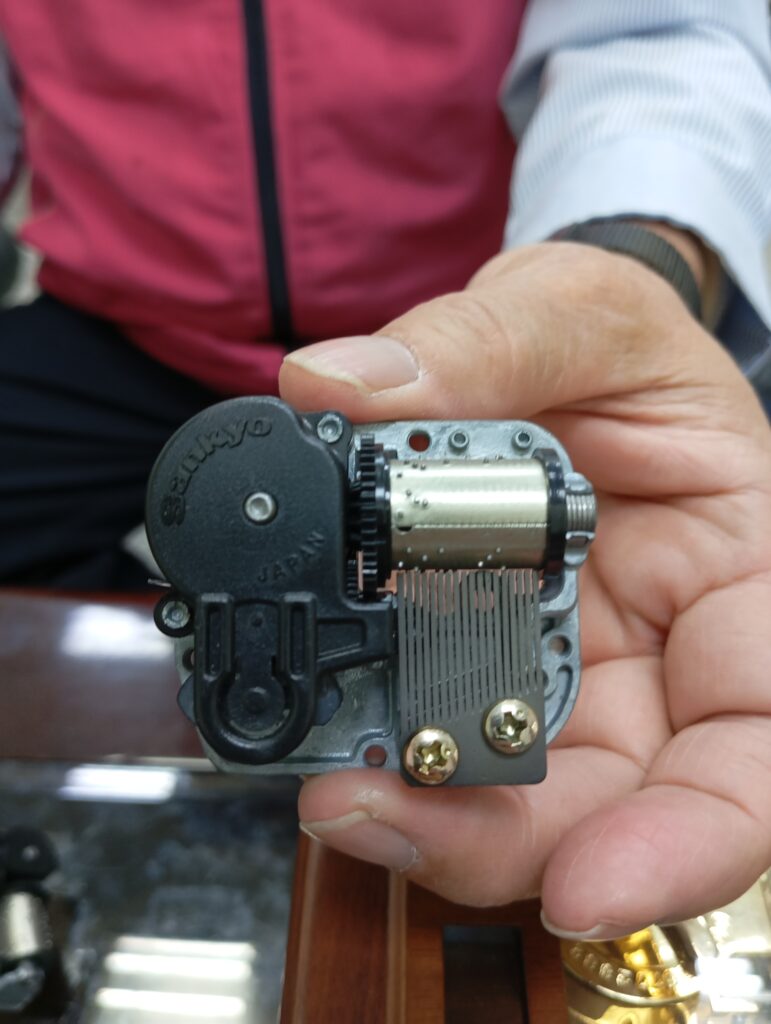

Sankyo’s first-generation music box model was designated “1S”, with a cast iron base. However, cast iron lacked the precision needed for automated production, so it was later replaced with die-cast zinc alloy. This solved the precision issue and was coded as “2S”, becoming the main music box model for Sankyo at the time. (Note: The “2S” model is identifiable by the fact that all its components are made of metal; the movement is entirely metal.)

The first model produced by Kyooh was the “2S” (the one displayed on the wall at the Wufeng Music Box Museum as the “Factory Opening Commemoration” is a 2S). Sankyo allowed the 2S to be produced in Taiwan because the Malaysia plant’s capacity was insufficient to meet market demand, and Taiwan could help reduce Japan’s high labor costs. Initially, the Taiwan plant only performed assembly—it did not manufacture parts. Kyooh had no equipment like punch presses for production; all components were imported from Japan, and Taiwan’s role was to assemble and ship the completed movements to distributors and music box manufacturers.

Localization of the “2S” Music Box in Taiwan

In 1979, the first year of Kyooh’s establishment, the company was only responsible for assembling movements, with all production lines and components imported from Japan. It wasn’t until the second year that Kyooh established a “Mechanical Department.” Initially, punch presses were used to produce the “music cylinders,” and later, die-cast zinc alloy production for the bases began in collaboration with Hexing Precision Metal Casting in Taipei, adding processes like tapping and drilling on the bases. Except for the vibration plates, which still needed to be imported from Japan, the rest of the components began to be locally manufactured in Taiwan.

However, punch press molds for the music cylinders still had to be imported from Japan due to the specialized music encoding techniques and the precision required for music box movements—a practice that continues to this day. As for zinc alloy base molds, the process started with Japanese molds, then gradually shifted to local production trials in Taiwan. These trial molds were sent back and forth to Japan for inspection and modification until they successfully passed Sankyo’s approval, allowing the use of locally produced zinc alloy bases.

Starting from Imitating Japan

Rather than “developing” music boxes, the early work in Taiwan was really about “imitating” Japanese production. Japan provided the blueprints, and Taiwan had to follow them 100% in manufacturing. Even screws for the vibration plates were only sourced locally in Taiwan after several years. As for the music box springs, although the parent company Sanho already produced springs for timers, they were only later allowed to be used in music box components.

The real challenge was not a lack of technical ability in Taiwan, but the Japanese side’s extreme caution. Any design or production changes required repeated testing and careful evaluation. As a result, music box development was a gradual, highly controlled process under strict Japanese oversight—it wasn’t simply a matter of Japan setting up a factory and Taiwan immediately designing and producing music boxes independently.

Japan’s Ambition to Dominate with the “3S”

At that time, annual production of the 2S model in Japan was 12 million units, combined with 6 million from Taiwan and 6 million from Malaysia—a total of 24 million units. This still couldn’t meet Taiwan’s local demand of 30 million units, let alone the global demand of 90 million units. The supply-demand gap was enormous!

As a result, Sankyo began full-scale development of a fully automated model, designated “3S”, and launched a new round of rationalized design. The 3S featured a smaller overall movement, with the mainspring barrel and gears changed from metal to plastic. This reduced costs and made the movement more suitable for mass production. The fully automated 3S model also applied for invention patents in the United States, Japan, the EU, and other countries worldwide.

The Discontinuation Crisis of Taiwan’s “2S”

After full-scale production of the automated 3S began, even though Taiwan had started producing all 2S components locally, the production cost of Japan’s 3S was still lower than Taiwan’s 2S. Additionally, because the 3S had a heavy plastic feel, the metal finish of the older 2S movements remained appealing for music boxes with exposed movements. In response, Japan developed the “2.5S” model.

The 2.5S replaced all transmission gears with the plastic gears from 3S, while retaining the 2S base and metal mainspring barrel. This reduced costs while allowing the movement to be plated in various vibrant metallic colors.

To focus on promoting the new 2.5S and 3S models, Taiwan’s 2S product line was forced to be discontinued.

Introducing the “Mini Movement” Sparks a Financial Crisis

To fill the gap left by Taiwan’s discontinuation of 2S, Japan transferred the assembly line for the mini movement to Kyooh, though all components continued to be produced in Japan. At that time, annual sales of the mini movement were still around 4 million units.

Unexpectedly, after introducing the mini movement, Kyooh began incurring consecutive losses, accumulating nearly NT$60 million in three years.

The reason was contractual: Kyooh had to purchase each mini movement component set from Japan for NT$30, but the assembled units had to be sold back to Japan for only NT$28 (the numbers are illustrative for easy understanding).

In other words, after buying raw materials from Japan for assembly, Kyooh was forced to sell the finished product back at a loss. Simply calculating material costs, the company lost money on every unit—selling 4 million units meant a loss on all 4 million!

A Forced Loss-Making Transaction

At the time, General Manager Huang Long-Xi, then factory head, raised objections to the Japanese manager of Kyooh’s administration department, arguing that the arrangement was completely unreasonable—who would run a business this way? To his surprise, the manager replied that he had no choice, because the sets of components sold by Sankyo to Kyooh at NT$30 were themselves sold at a loss!

Who would believe such a claim? Who would deliberately set a loss-making price? The Japanese manager explained that the selling price was not based on cost, but on market-expected pricing. Although mini movements cost more to produce than 3S movements, their smaller size meant the finished music boxes were smaller, and customers’ expected price for them was lower. Hence, the price had to be set accordingly, or the product wouldn’t sell.

In reality, Sankyo’s use of market-expected pricing forced Kyooh to sell below direct cost, causing consecutive losses for Taiwan’s Kyooh.

Introduction of the 20-Note TDM Model

With the 2S discontinued and the mini movements incurring losses, what could Taiwan’s Kyooh do? The only option was to renegotiate with Japan and decide to introduce the TDM model to Taiwan.

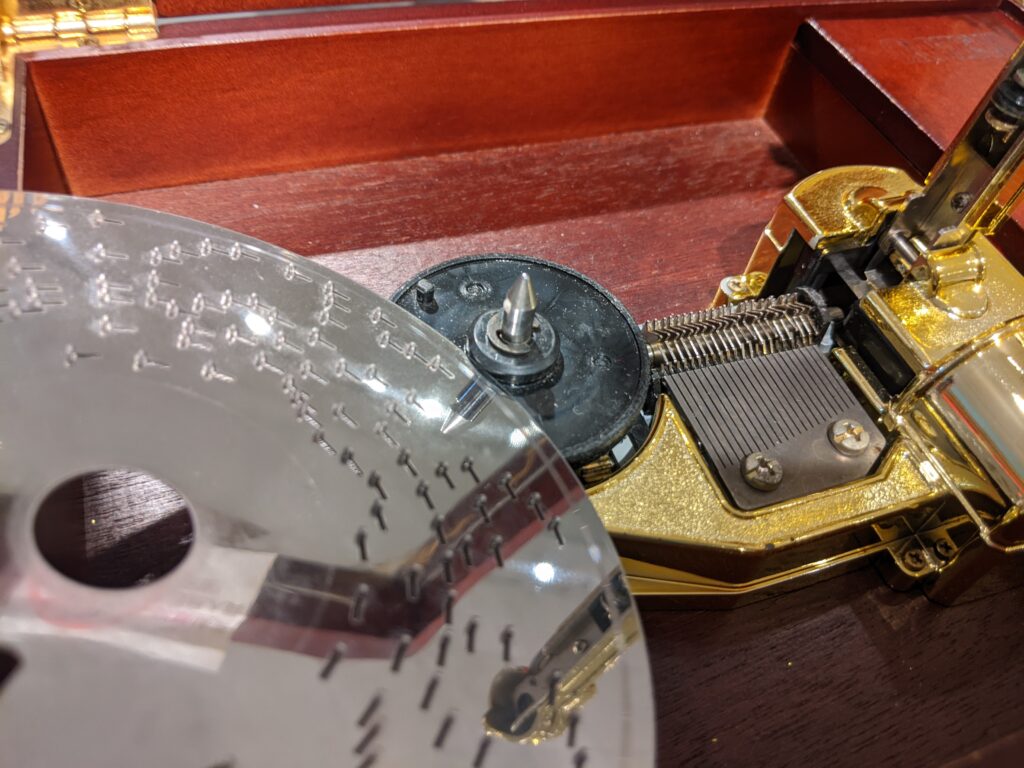

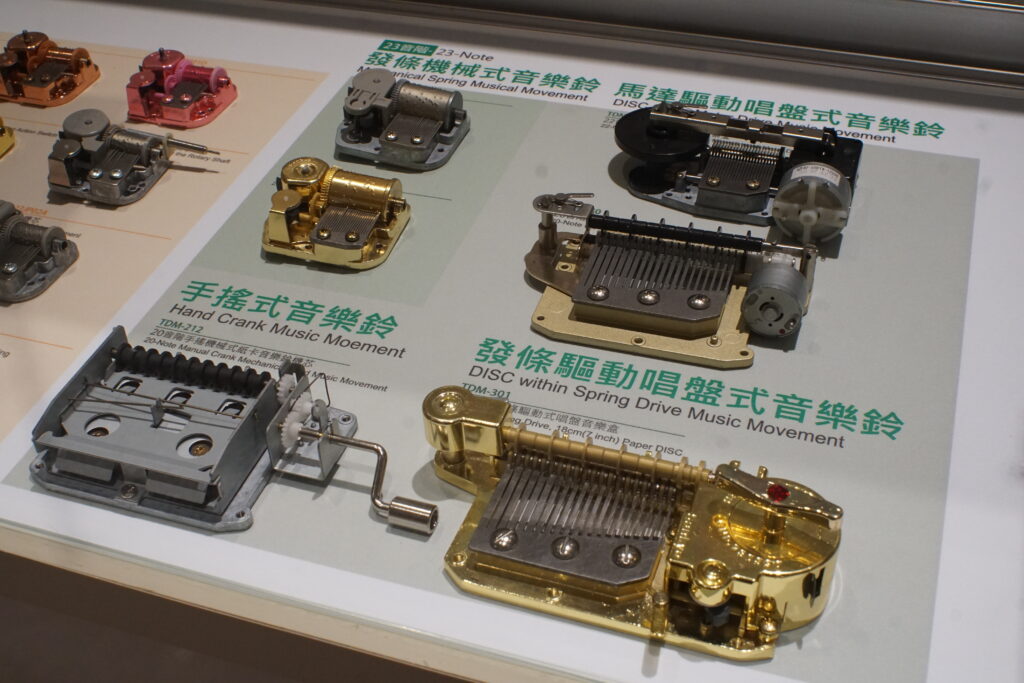

The TDM (MOTOR DRIVE DISC PLAYER) model is a 20-note, motor-driven music box, commonly seen as the disc-type music box. Later, paper strip music boxes were also categorized as TDM models, and the same vibration plate design was eventually used in Muro Box.

There is also a smaller stainless-steel disc version with more notes—22 in total—also classified under TDM. However, due to its smaller vibration plate, it doesn’t sound as full as the 20-note TDM.

For these TDM models, except for the vibration plates—which were produced in Japan and tuned in Taiwan—everything else, including the discs, was manufactured locally in Taiwan.

The main orders for TDM came from Sankyo’s Hong Kong branch, fulfilling orders for the U.S. brand Mr. Christmas, a well-known mail-order music box company. At its peak, orders for motor-driven TDM units reached as high as 150,000 per year.

Challenges with Mr. Christmas Orders

However, fulfilling Mr. Christmas orders came with its own challenges. Their annual order of 150,000 units had to be delivered within just three months—May, June, and July. But the production speed of Japanese vibration plates was only 600 per day, requiring a total of 250 days to produce. This made it impossible to supply on demand, as the vibration plate capacity was too low.

The only solution was to pre-order the entire year’s required vibration plates, with Japan delivering them gradually each day. This, however, resulted in nearly a year’s worth of inventory sitting at Taiwan’s Kyooh, placing additional pressure on cash flow.

The Japan Trip for Mini Movements

Meanwhile, the mini movements continued to incur losses, and the TDM model couldn’t make up for them—the company was barely hanging on. After much consideration, General Manager Huang (then factory head) refused to believe that the mini movement components were being sold at a loss to Kyooh in Japan, and kept raising the issue. Unable to convince the Taiwanese side, Sankyo finally said:

“Mr. Huang, if you don’t believe it, you are welcome to come to Japan and see for yourself.”

Japan Was Really Selling Mini Movements at a Loss

“In December that year, it snowed, and I resolutely went to Sankyo’s Shimosuwa factory in Japan. They opened up their computer and went through each part one by one, showing how many units they could produce per hour, the material cost for each, the processing cost…

Sure enough, the total cost added up to over 30 yen, so selling them to us for 30 yen was indeed at a loss!”

So, what could be done?

Transferring Mini Movement Production to Taiwan

“Mr. Huang, why not move the specialized equipment for mini movement production to Taiwan? Wages are lower there, so costs should decrease.”

“But we can’t just send the machines over. They need to be refurbished, and old parts replaced. That alone would cost around ¥70 million. Additionally, machines shared with the 3S cannot be moved; new machines would need to be custom-made, costing another ¥70 million.”

This meant an investment of over ¥100 million. Taiwan’s factory didn’t even have enough space, requiring a new building. Even without considering equipment costs, if the machines were actually moved to Taiwan, how much production cost could really be saved?

A Loss-Making Task That Couldn’t Be Avoided

After careful calculation, production costs could only be reduced from over 30 yen to 28.5 yen per unit. But the selling price to Japan was 28 yen, meaning that even if the components were produced in Taiwan, Kyooh still lost 0.5 yen per unit!

Kyooh faced only two options: either abandon mini movement production and focus solely on the TDM model, which still had annual orders of 150,000 units and remained profitable, or continue producing mini movements at a loss.

However, the Japanese side would not agree. Sankyo still had millions of mini movement orders each year and needed someone to manufacture them. But producing them meant a guaranteed loss. Kyooh’s capital was NT$20 million, and losses had already accumulated to nearly NT$60 million—continuing was simply unsustainable.

Taiwan Develops Its First Original Music Box Movement

Since Japan wouldn’t agree, Kyooh had no choice but to take the second path: redesign the mini movement in Taiwan without Japanese interference.

Previously, even changing a supplier required five to six months of approval from Japan, but if things continued that way, Kyooh would have no chance to solve the problem.

“I’ll figure out how to reduce costs myself, but don’t interfere. I’ll take full responsibility for the outcome.”

In fact, before traveling to Japan, the general manager (then factory head) had already planned the redesign, which gave him the confidence to insist on no interference. With no other options, Japan ultimately agreed.

Upon returning to Taiwan, the general manager immediately hid in the development room with Section Chief Chang to start working.

“I told them, if you want to reach me, you only have half a day—mornings don’t count. I’m responsible for developing the new mini movement with Chang!”

“Actually, it was quite simple. I just learned from the 3S approach. They switched from metal to plastic, so why can’t I? The gears were originally metal; in the mini movement, they were metal too. I just changed them to plastic!”

The “All-in-One” Design Concept

The general manager explained that Japanese developers had a common trait: at the start, they designed products as if to protect themselves—making them extremely sturdy and “perfect”—then only gradually rationalized the design. By the time costs were significantly reduced through rationalization, many years had often passed.

Back in Taiwan, it took about six months to completely redesign the mini movement. Just then, Japan sent a message:

“Okay, even though you asked us not to interfere, can we offer support?”

“Support is fine, of course,” he replied.

So Japan sent an engineer to assist Kyooh. Although the new mini movement design was already nearly complete, it was still useful for them to observe and provide input.

A Culmination of Taiwan-Japan Collaboration

Who was this engineer? He was Mr. Isaka Akihiko, the Japanese Sankyo designer of the 3S model. He stayed for two weeks, spending days discussing the design with Kyooh and evenings being taken out to dinner and escorted back to his hotel. During those two weeks, the entire mini movement design was thoroughly revised and refined.

The main modifications focused on the accessories of the music box movement, such as the side and central rotating components. Originally, the base required an additional metal plate, which had to be punched and fitted with multiple transmission gears. With many different models, each required its own specification for the added plate and base.

So they brought all the models together and integrated the areas requiring the extra punched metal plates into the new base. As a result, for essentially all accessory models, there was no longer a need to add that extra metal plate—parts could simply be placed and used.

“This modification significantly reduced costs.”

Business Strategy to Protect Taiwan’s Profits

The primary goal of developing the new mini movement was to quickly recover the significant past losses.

“So we added a safeguard in our cost estimates.”

For example, if a modification could realistically reduce costs by 10 yen, the report conservatively stated only a 6-yen reduction. This was done to prevent Japan from immediately demanding a lower supply price.

At the same time, Kyooh’s Taipei sales department was informed that the new mini movement was ready for mass production. Although costs had been rationalized, the updated cost sheet was deliberately withheld from the sales department, citing ongoing production adjustments. The sales team was instructed to continue selling at the old mini movement price.

Turning Losses into Profits

At the start, the new mini movement was sold at the same price as the original model. With reduced production costs, Kyooh naturally began turning a profit. Sales were kept low-key and steady, with monthly orders reaching nearly 400,000 units. In less than three years, the previous NT$60 million loss was fully recovered.

Japan also understood that Kyooh had incurred losses on this model for three consecutive years. Only after confirming that Kyooh had returned to profitability did Japan begin requesting price reductions.

By this time, due to years of losses, Sankyo had reduced its stake in Kyooh to just 14.9%, returning full management control to the Taiwanese side. The general manager position no longer required Japanese assignments. Following this turnaround, Huang Long-Xi naturally assumed the role of the new general manager.

(Note: For Japanese overseas joint ventures, holding more than 15% would require including the subsidiary’s revenue in Japan’s total accounts. Since Japan had been operating at a loss, reducing its stake to 14.9% prevented Taiwan’s losses from being consolidated into the Japanese parent company’s accounts.)

Deceiving Even One’s Own Team?

After assuming the role of general manager, the mass production of the new mini movement was on track. To ensure transparency in management, he recreated the cost calculation sheet for the new mini movement and sent it to the Taipei sales department.

The sales manager was shocked by the numbers—costs had dropped so much, no wonder there was a profit! Why hadn’t the sales team been informed earlier? After all, knowing the real cost is essential for negotiating with customers.

However, the general manager understood the mindset of salespeople: the cheaper the product, the easier it sells. If the true cost had been revealed, the new mini movement, capable of yielding significant profit per unit, would likely have been sold at a lower price automatically. But that wasn’t necessarily beneficial—the market for mini movements was limited, and lower prices wouldn’t guarantee higher sales volume.

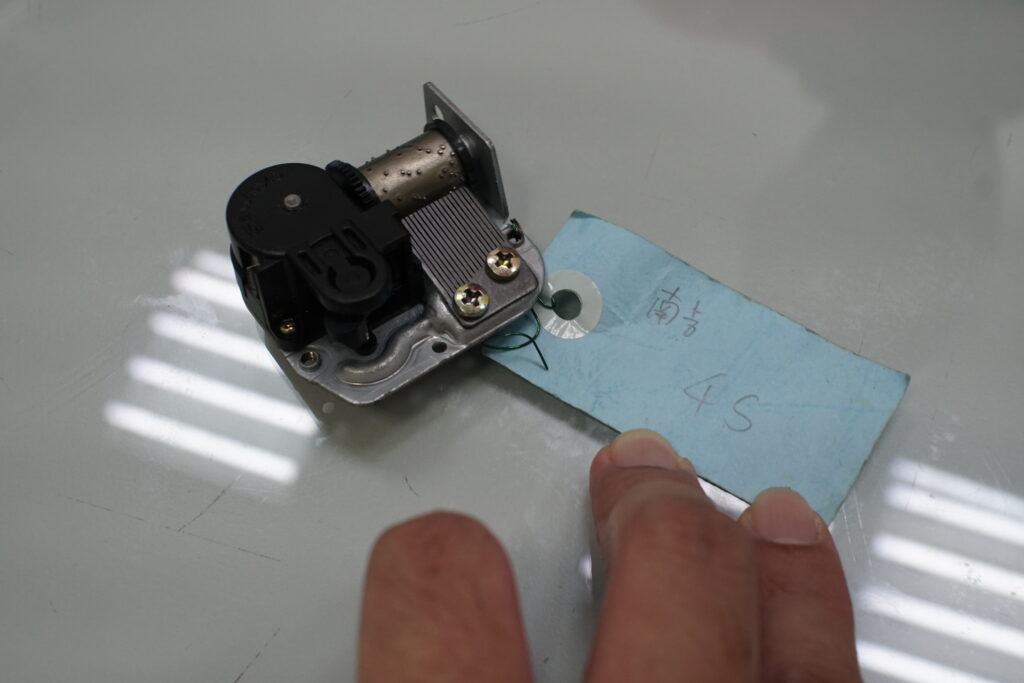

Mini Movements: Taiwan’s First Fully Original Music Box Design

The mini movement was, in fact, the first music box movement truly developed by Kyooh itself. After investing around NT$11 million in new component molds and production line modifications, and relocating Japan’s automated vibration plate machinery to Taiwan, all mini movements worldwide began using the version developed by Kyooh, now 100% produced in Taiwan.

“This single product kept Kyooh profitable for ten years.”

Facing Counterfeits

At the time, when the music box industry was still thriving, several factories in mainland China were imitating Kyooh’s mini movements. For example, a music box competitor once ordered 70,000 mini movements from Kyooh. The general manager thought it was a sign that their business was doing well—such a large order.

However, after delivery, they were suddenly informed that the batch had an unusually high defect rate: 1,200 units were deemed defective.

Puzzled by the high defect rate, Kyooh initially had to take the defective units back. Upon inspection, quality control found that only 70 units bore the Sankyo trademark—the rest, over 1,100 units, had the TOYO trademark! The counterfeiters had imitated the mini movements so precisely that they accidentally mixed their own defective fakes into Kyooh’s shipment.

Why the Mini Movement Declined After Ten Years

Although most orders came from Hong Kong, Kyooh’s highly rationalized design made it easy for downstream manufacturers to replicate the music box components themselves. While they continued ordering the basic movements, they secretly began producing the parts on their own.

Soon after, mainland China’s Yunsheng factory figured out how to produce mini movements as well. Because it was profitable, many manufacturers openly copied the design. By then, Kyooh’s patents had expired, leaving no legal way to stop them. Under this wave of fierce competition among numerous manufacturers, sales eventually began to decline.

The Story of Mr. Christmas

While the mini movement story was unfolding, Kyooh also had another product line: the TDM (MOTOR DRIVE DISCPLAYER), which refers to 20-note motorized music boxes, including disc-type and paper strip music boxes.

For the 20-note TDM models, all components except the steel vibration plates (imported from Japan) were produced and assembled by Kyooh in Taiwan. However, all parts were manufactured strictly according to Sankyo’s design drawings. In other words, TDM was a Japanese-designed model, with Taiwan acting as the contract manufacturer, since Japan no longer produced them.

In terms of sales, TDM essentially had only one buyer: the American brand Mr. Christmas. Orders were placed through Sankyo Hong Kong, and Kyooh received the orders from Hong Kong and handled the actual production.

But TDM orders, which once peaked at 150,000 units per year, eventually plummeted to nearly zero. What happened? Here begins the story of Mr. Christmas and the TDM music box OEM.

Mr. Christmas’ Price-Cutting Strategy

Although Mr. Christmas had massive sales volume, the company was extremely demanding with its suppliers. One of the most notorious practices was requiring suppliers to lower their prices by more than 10% every year. Despite the challenge, suppliers generally complied because the orders were so large.

Faced with such demands, Kyooh had little choice but to move the TDM production line from Taiwan to mainland China to reduce costs while maintaining profitability. However, this annual price-cutting practice wasn’t limited to the music box movements—it applied to wooden boxes, accessories, and all other suppliers as well.

The Fatal Temptation of Orders

Originally, Mr. Christmas’ wooden box supplier was Hai-Shan, the factory run by the father of the owner of Puli’s “KoKoWu”(敲敲木工房).” They had a factory in Huizhou, China, dedicated to fulfilling Mr. Christmas orders. With such stable demand, the factory grew to nearly 2,000 employees. However, unable to endure the annual price-cutting demands, they eventually refused further orders and withdrew back to Taiwan.

To further reduce costs, Mr. Christmas then outsourced production to a mainland Chinese company called Chuang-Yi. But the same strategy—cutting prices by over 10% annually and delaying payments under various pretexts—led Chuang-Yi to collapse as well.

As a result, Mr. Christmas’ reputation among contract manufacturers was thoroughly damaged. No large wooden box factory was willing to take their orders anymore, causing the company to gradually exit the large music box market.

Thus, the disappearance of Mr. Christmas’ large music box products wasn’t due to declining sales, but the consequences of excessive pursuit of profit. At the same time, Kyooh’s TDM orders also sharply dwindled alongside the disappearance of large-scale wooden box suppliers.

TDM Improvements in Taiwan

After Mr. Christmas stopped producing music boxes and began canceling orders, Kyooh faced a large backlog of TDM vibration plate inventory. To make use of these TDM components, Kyooh’s developers began creating new products based on the TDM platform.

For example, the paper-disc music box model was developed in Taiwan. Originally, the disc was made of PVC, driven by a rubber wheel. Over time, the disc would slip because the rubber aged and wore down.

The developers realized the rubber wheel wasn’t durable, as it eventually left behind worn powder. So they removed the rubber wheel and added square holes to the disc, switching to a gear-driven mechanism. This optimization was entirely done in Taiwan by Kyooh. Some orders from Japan, such as CITYZEN musical clocks, still use the original rubber-wheel design.

Spring-Driven Disc Music Boxes

Originally, disc music boxes all used motors. Considering that most people wouldn’t listen to a music box continuously all day, Kyooh developed a spring-driven version. The spring was originally designed for Japanese baby crib music boxes, with a length of 180 cm and a full rotation playing 20 minutes of music. Kyooh adapted it for the disc music box, adjusting it so that a full winding would rotate the disc for six minutes. This model holds patents in the U.S. and China, and was later also sold in Japan.

It’s important to note that although these designs were developed by Kyooh in Taiwan, the products carry the Sankyo brand. This is because Sankyo held shares in Kyooh, and Kyooh had obtained licensing rights to use the Sankyo brand.

“3S”: The Pinnacle of Sankyo’s Ambition

Sankyo invested 45 billion JPY to build a fully automated factory for the 3S model in Hara Village, Suwa District, Nagano Prefecture, Japan. Simply put, trucks would deliver metal blocks and plastic pellets, and what came out were complete music box movements.

The factory was enormous, featuring three fully automated production lines. This represented the peak of Sankyo’s ambition in music box manufacturing, but it also marked a turning point toward the decline of Japan’s music box industry.

The 3S Fully Automated Production Line: A Misguided Decision

When Japan moved the 2S model production to Taiwan, it was already operating on a semi-automated production line. If they had simply continued producing 2S or 3S on a semi-automated line in China instead of investing in a fully automated 3S line, companies like Yunsheng might never have emerged.

At the time, the monthly wage in China was only 100 RMB. The 45 billion JPY investment in automation could have paid thousands of workers annually through depreciation alone, making a fully automated line unnecessary.

A few years after the 3S fully automated factory was completed, Yunsheng had already set up in China. When personnel from Kyooh visited Yunsheng, they were shocked to see hundreds of workers hand-tuning vibration plates simultaneously, showcasing the power of labor-intensive methods over costly automation.

Labor Was Actually Cheaper Than Machines

In the end, the fully automated 3S production line in Japan cost more than producing the same units in China using labor-intensive methods. High expenses for equipment depreciation and maintenance made the automated line less competitive in price. As a result, orders dropped, and the automation could never run at full capacity. Japan was left with no choice but to adjust in response to Chinese competition.

Sankyo Asked Kyooh to Set Up a Factory in China—but Failed

After Sankyo’s 3S automated production was undercut by Yunsheng’s low-cost manual strategy, production collapsed. Even Sankyo’s own Guangzhou plant abandoned music box manufacturing. Sankyo tried suing Yunsheng in a Henan court for patent infringement, but since Yunsheng functioned almost like a state-owned enterprise, the lawsuit predictably failed.

Desperate to compete on price and continue serving long-time Sankyo music box customers, Sankyo asked Kyooh to set up a large-scale 3S production base in China with 2,000 workers, targeting 30 million units per year.

Kyooh, however, assessed that by then Yunsheng was already well-established and that the Chinese market was flooded with unbranded knockoffs. Seeing no first-mover advantage, Kyooh declined the request to build a 3S factory in China.

Sankyo’s China Factory Run by Nanji

With Kyooh declining to set up a factory in China, Sankyo turned to Nanji, Taiwan’s largest music box distributor at that time. Since Sankyo was planning to halt 3S production in Japan and Kyooh had no interest in a China facility, Nanji—whose core business was selling music boxes—faced the risk of losing its main product line. Reluctantly, Nanji agreed to establish a factory in China.

Kyooh even assisted Nanji by setting up the first 3S production line in China and training the initial batch of employees. With Sankyo’s Guangzhou plant already shut down, Nanji became Sankyo’s sole manufacturer and distributor in China, reaching an annual output of 20 million units.

Kyooh’s Decision to Set Up a Factory in Dongguan, China – Reason 1

After Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening-up, many foreign companies started investing and producing in China. At that time, Kyooh worked with around 100 suppliers, all handling very large orders. Unexpectedly, over 90 of them moved their operations to China.

Initially, most Taiwanese businesses settled near Guangdong, so Kyooh didn’t feel the need to follow—shipping from Taiwan to China seemed sufficient. Even when Sankyo requested Kyooh to produce 3S models in China, Kyooh remained unmoved.

However, as Taiwanese businesses spread to Tianjin, Beijing, and even Sichuan, customers began complaining that shipments from Taiwan took too long. Combined with tariffs and a 30%+ VAT, profits were heavily eroded. With the entire upstream and downstream supply chain relocating to China, Kyooh had no choice but to establish a factory in Dongguan, directly serving Taiwanese businesses and expanding its operations on-site.

Kyooh’s Decision to Set Up a Factory in Dongguan, China – Reason 2

After Sankyo’s Guangzhou factory, which produced 3S and 2.5S models, shut down, the Chinese company Nanjie took over the lower-cost, high-volume 3S production but abandoned the 2.5S model. The 2.5S retained the metal look of the 2S, could be plated gold or silver, and was ideal for music boxes where the mechanism is visible. However, its higher production cost and smaller quantity made it less attractive.

At that time, Kyooh’s sixth general manager, Maruyama, who had been the last GM of Sankyo’s Guangzhou factory, thought it was a pity that Nanjie abandoned 2.5S, since the Guangzhou factory still had an annual market demand of 2.5 million units. Despite the higher cost, the added value justified production. He proposed that Kyooh set up a factory in China to take over 2.5S production.

At the same time, labor-intensive TDM models could also be shifted to the Chinese factory, taking advantage of low wages to optimize costs and generate profits.

Consequently, in January 2002, Kyooh officially began music-spring production in Qishi Town, Dongguan, Guangdong Province.

Japan’s Cost-Reduction Measures for the “3S” Model

To lower costs, Japan commissioned Kyooh to rationalize the 3S base, reducing its weight from 40 g to 36 g. The production of the base was shifted to suppliers in Taiwan and China, and other components—such as gears and plastic spring covers—were also sourced from the two regions.

At Kyooh’s China factory, these parts were pre-assembled into a semi-finished state (without the vibration plate and cylinder) and then sent to Japan for final assembly. The cylinder and vibration plate production and tuning still used parts of the original fully automated Japanese production line.

Previously, the spring covers were stamped with “Sankyo Japan”, but since they were now produced in China, regulations prohibited marking them as “Japan.” Consequently, the covers were labeled simply “Sankyo”, while the Japanese origin was indicated on the newly designed packaging produced in Japan.

Japan’s Failed “4S” Model

In addition to the fully automated 3S model, Japan also developed a fourth-generation 4S model. The motivation was cost reduction: the price of zinc alloy for the base had risen significantly, so they switched to stamped iron sheets for production.

However, customers did not accept it. Because the 4S base was made from stamped iron, the limited height forced the vibration plate to be installed at an angle. This compromised the overall aesthetics, making the product feel less premium and less appealing to consumers.

The failure of the 4S was therefore not due to sound quality, but because the appearance was unattractive to customers.

Taiwan’s Kyooh “5S” Model Development

Amid the intense price competition between China’s Nanji “3S” and Kyooh’s own “2.5S”, and with the approval of joint venture Japan Sankyo, Kyooh in Taiwan independently developed the “5S” model, deliberately changing the case color to green to visually distinguish it from the black “3S” model.

The 5S addressed all the shortcomings of the 3S. For example:

The green mainspring cover was reinforced to protect the stop lever, preventing damage.

The base weight was reduced from 41g to 30g, significantly lowering costs without compromising quality.

After development, Kyooh sent ten 5S samples to Japan for blind comparison against the 3S. The result: all Japanese engineers could not distinguish any quality difference, proving the design was a success. Despite weighing only 30g (compared to 41g for 3S), the 5S maintained the same performance, achieving both cost reduction and quality retention—a significant technical accomplishment.

The 5S model also received development subsidies from Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs Industrial Development Bureau under the 2009 Traditional Industry Technology Development Program, and Kyooh applied for patents to protect against aggressive competition from China’s Nanji and other no-brand manufacturers.

The successful mass production of the 5S became the mainstay model for Kyooh’s 18N music box movements.

“5S” Even Surprised Japan

Eventually, the head of Sankyo Japan’s sales department personally asked Kyooh Taiwan how they managed to achieve it—what was the key breakthrough in the design?

General Manager Huang replied:

“Do you think I would explain the breakthrough in detail?”

“I said I cannot describe the exact key points, but we accomplished it through our effort.”

The floral patterns on the green mainspring cover were also a result of Japan–Taiwan collaboration. After seeing the samples, the Japanese suggested that engraved patterns would look better and provided drawings for Kyooh to implement.

Although Japan Sankyo did purchase some 5S units, their domestic sales still primarily focused on the 3S model—designed by Japan, and produced using the semi-assembled components from Taiwan or China, with final comb and cylinder assembly completed at the factory in Nagano Prefecture’s Suwa District.

Relationship Between Kyooh Taiwan and Dongguan Factories

The Kyooh Taiwan factory and the Dongguan (China) factory operate under a division-of-labor system. The Taiwan factory took over the automated production line for Japan’s mini music movements and is mainly responsible for producing the vibration plates, including stamping, cutting, grinding, and tuning. The factory has two fully automated lines. The music cylinders for mini movements are also produced in Taiwan and then supplied to Dongguan for assembly. In short, the Taiwan factory produces the key components, while the Dongguan factory handles assembly.

Although Japan requested that part of the mini movement’s automated production line be moved to Dongguan, the current system represents a cross-strait collaborative workflow. Overseas orders are shipped from Dongguan, while orders for Taiwan remain produced locally in Wufeng, albeit in smaller quantities.

Were there other music movement factories in Taiwan?

When Mr. Huang served as a director of the Taiwan Toy Association, he had heard that because the demand for music movements in toys was so large, the association had once considered commissioning the Industrial Technology Research Institute to develop and produce music movements. However, it is unclear whether the project failed or was never actually carried out, and in the end, nothing came of it.

Therefore, prior to the emergence of Kyooh, Taiwan did not have any factories that produced music movements. After Kyooh appeared, the general manager was notified twice by suppliers that competitors were attempting to create molds to imitate music movements, but none of these attempts ever reached the market. In other words, although some Taiwanese factories had ambitions to produce music movements themselves, they never truly succeeded.

The only concrete information known is regarding Japan’s Toyo music movements. It was heard that Toyo planned to cooperate with a Taiwanese music movement distributor, Gao Mei Company, to establish a factory called Hua Mei in Beitou, Taipei, to produce Toyo-branded music movements. From the general manager’s perspective, however, he had never seen any actual products being produced. It is only known that Hua Mei later moved to Tianjin, China—the same factory that previously imitated mini music movements—and continued producing Toyo music movements. Hua Mei has since ceased operations and, according to reports, was sold to local Chinese owners under a new name.

Letting More Taiwanese Know the History of Music Movements

In Taiwan, Kyooh is the only factory producing music movements, and it has been operating for more than forty years. Very few people actually know how many music movements have been supplied to music box distributors in Taiwan and exported around the world. Most Taiwanese don’t even know what a “music movement” is—they only know the music box. And when it comes to music boxes, their understanding is usually limited to just two types: dancing dolls and jewelry boxes.

Even when the Wufeng Cultural Association was being established, the Lin Family Garden was leading the initiative. At that time, the executive director of Lin Family Garden went to Kyooh to see Mr. Huang, the general manager:

“I heard we have music movements being produced in Wufeng?”

“Yes, it’s been over forty years.”

“How come I never knew about this?”

Kyooh Had Very Little Direct Contact with Consumers

Kyooh’s customers were all businesses—they bought the music movements, installed them in boxes, and sold them as finished music boxes. There weren’t many customers, only about a hundred or so, all of them music box manufacturers. Naturally, anyone who needed to buy a music movement would come directly to Kyooh. There was no need for advertising, which is why most people didn’t know about them.

In fact, very few people realize that music movements come in a variety of scales: 18-note, 12-note (this was an option in the 2S era; after the 3S model was introduced, production standardized to 18-note, so 12-note was discontinued), 20-note, 22-note, 23-note, 50-note, 70-note, and even over 100 notes. But who knows that? Most people don’t.

“It’s necessary to let everyone know that music boxes come in all these varieties—not just dancing dolls and jewelry boxes.”

The Process of Establishing the Modern Music Movement Museum

The building chosen for the museum was originally a factory for electronic music movements. After the production lines were removed, the space became vacant.

Between 2015 and 2017, this period coincided with a wave of retirements among Kyooh’s senior employees. To address the retirement fund obligations (under the old Labor Standards Act, companies were required to fully set aside retirement reserves in a lump sum), Kyooh sold part of its land.

With a significant reduction in personnel and empty factory space, electronic production had ceased, and the number of mini music movements had also declined considerably. At this point, the question of whether Kyooh still had value in Taiwan was put squarely on the table.

Back in 2010, the general manager had already started thinking about setting up a museum. But how could all the documents and the various types of music box samples be collected? In the past, the customers who bought music movements from Kyooh would assemble them into music boxes and keep a few samples on display shelves.

“I went to each of them one by one, asking, ‘Can you give me one of your old pieces? Or can I buy it from you?’”

Of course, some were too polite to accept money, so gradually, over the course of several years, the collection grew. Most of the museum’s current holdings—the majority of the music boxes on display—were collected during those years by the general manager, personally visiting customers. If he saw antique music boxes being sold or listed on Facebook, he would drive there with Manager Lin Li-Mei, inspect them in person, and add them to the museum’s collection.

Our Expectations for the Modern Music Box Museum

Overall, the decline of the music box industry has been a relentless process. Beyond the U.S. copyright lawsuits and low-priced dumping from mainland China mentioned earlier, other recurring challenges Kyooh often faces include China’s anti-luxury policies, the impact of the pandemic, wars, and U.S. tariffs. Taiwan’s music box industry had already collapsed long ago. Today, it is not a matter of thinking about how to revive it, but rather quietly observing when the “stop” button will finally be pressed.

After these years of reflection, we have gradually come to understand that perhaps following the natural course of time is the way of the world. Music boxes began in Europe, then moved to the U.S., Southeast Asia, Japan, Taiwan, and finally to mainland China. Rather than dwell in nostalgia, what we need to do is document and preserve everything that still exists today.

As General Manager Huang Long-Xi said in a recent interview:

“Music box movements are made in Wufeng, Taiwan.” People need to know this because for over 40 years, there have been so many kinds of music box movements, and Kyooh is the only one factory in Taiwan. Therefore, Kyooh needs to establish a museum, to preserve this culture and this history, and to carry forward Taiwan’s unique heritage of music box movements.”